Volume 8, Issue 1 (Journal of Clinical and Basic Research (JCBR) 2024)

jcbr 2024, 8(1): 19-21 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Norouzi Allahleh Korabi M, Jokar A, Qaraaty M. A case report of successful treatment of abdominal pain with umbilicus visceral manipulation. jcbr 2024; 8 (1) :19-21

URL: http://jcbr.goums.ac.ir/article-1-430-en.html

URL: http://jcbr.goums.ac.ir/article-1-430-en.html

1- Department of Midwifery and Reproductive Health, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

2- Persian Medicine Department, Faculty of Medicine, Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran

3- Department of Traditional Medicine, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran; Clinical Research Development Unit (CRDU), Sayad Shirazi Hospital, Golestan University of Medical Sciences, Gorgan, Iran ,gharaaty1387@yahoo.com

2- Persian Medicine Department, Faculty of Medicine, Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran

3- Department of Traditional Medicine, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran; Clinical Research Development Unit (CRDU), Sayad Shirazi Hospital, Golestan University of Medical Sciences, Gorgan, Iran ,

Keywords: Abdominal pain, Umbilicus dislocation or displacement (Umbilicus), Navel therapy, Traditional Persian medicine (TPM) (Medicine, Persian), Case Reports

Full-Text [PDF 346 kb]

(539 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1236 Views)

Full-Text: (353 Views)

Introduction

Treatment in traditional Persian medicine (TPM) is based on 3 principles: preserving health, nutrition, and medication and therapeutic measures. Among these therapeutic measures, visceral manipulation is a significant approach.

Umbilical displacement, referred to as "Taharok-e Sorre" or "Soghoot-e Sorre" in TPM texts (1), signifies the incorrect positioning of the umbilicus, characterized by its slipperiness, fallen state, or knotting (2). TPM scholars have expressed various opinions regarding umbilical displacement (Taharok-e Sorre). One of them suggests that it is caused by the movement of the abdominal muscles near the umbilicus, resulting from intense and sudden movements (1).

The factors causing umbilical displacement include impacts, slipping of the feet, and lifting heavy loads (3). Symptoms of umbilical displacement include intestinal pain, twisting of the umbilical cord in the abdomen, constipation, changes in bowel movements, loss of appetite, excessive unquenchable thirst, and the inability to palpate the artery below the displaced umbilicus (1).

Umbilical dislocation or displacement is linked to various symptoms, including diarrhea, constipation, abdominal pain, anorexia, anxiety, and depression (2). According to TPM, these symptoms arise from structural changes, such as physiological and anatomical alterations, as well as the accumulation of gases and fluids in the umbilical and tail region, whether momentary or permanent. Consequently, the foundation of treatment is based on reducing gas production and enhancing fluid analysis (1).

Methods

History and clinical examination based on conventional medicine

The patient is a 35-year-old married woman (G2P2Ab0L2NVD2) with a height of 164 cm, a weight of 78 kg, and a body mass index of 29.10 (indicating that she is overweight). She resides in Gorgan, Iran. The patient presented with complaints of pain in the upper and lower left side of the abdomen, constant and non-radiating, accompanied by a high appetite and abdominal fat. She sought treatment at the TPM health care center affiliated with Golestan University of Medical Sciences on 21 February 2022.

Gastrointestinal history:

The patient did not report any postural pain or its association with eating. She had been experiencing fatigue, bruising, and somnolence for approximately 1 year. The patient mentioned that around 5 years ago, after her second childbirth, she started experiencing an increased desire for food and accumulation of abdominal fat, along with symptoms of depression. She had been receiving treatment with sertraline until the time of referral. Additionally, for the past year, she had been experiencing soft bowel movements occurring once every 2 or 3 days without complete excretion.

The patient did not exhibit symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, anorexia, or urinary complaints. However, she expressed dissatisfaction with the quality and uninterruptedness of her sleep. Her typical sleep period is from 11 PM to 6 AM.

In terms of menstrual history, the patient reported irregular and fluctuating monthly cycles. The bleeding experienced was of moderate intensity, and the presence of clots and dark blood was noted.

Past medical history:

The patient mentioned a previous diagnosis of hyperlipidemia.

Drug history:

The patient had been regularly taking 75 mg of sertraline (brand name: Acentra) daily for 1 year to manage her depression. No information was provided regarding the use of tobacco, alcohol, or smoking.

Family history:

The patient reported a family history of high blood pressure in her mother.

Allergy history:

The patient has no known history of allergic reactions to medications, seasonal allergies, or food allergies.

Surgery history:

The patient underwent gallbladder removal and curettage procedures in the past.

History and clinical examination based on TPM

According to Salmannejad's temperament questionnaire, the patient's primary temperament (Mezaj) was determined to be hot and wet (Garm-o-Tar), with a score of 56 for warmth and 11 for wetness (4). The patient had a fat body, white facial skin, and dark brown eyes and hair. Additionally, for approximately 1 year, the patient experienced soft bowel movements occurring every 2 to 3 days without complete evacuation.

During the clinical examination, the patient exhibited abdominal pain and a palpable pulse around the navel.

Healthy lifestyle measures

The initial therapy session took place on February 21, 2022.

During the session, the patient was provided with health-conscious recommendations based on TPM practices. Due to the patient's inadequate and irregular sleep patterns, it was suggested that she establish a consistent sleep schedule, specifically from 10 PM to 6 AM, and avoid excessive daytime sleep. Furthermore, the patient was advised to engage in regular physical activity, avoid prolonged periods of inactivity, and limit the consumption of yogurt, buttermilk, pickles, cucumber, and tomato salad. It was recommended that the patient consume meals at a leisurely pace, thoroughly chewing her food. To reduce water intake, the patient was advised to follow a diet consisting of olives, steamed vegetables, grilled meat, and fresh produce. Additionally, the patient received guidance on managing anxiety through deep breathing techniques.

During the initial session, in addition to lifestyle recommendations, the patient was prescribed the following treatments:

After each meal, the patient was advised to take 2 tablets of Qors-e-Balgham, followed by 1 Iaraj Fighra capsule in the morning while fasting (Table 1). These should be consumed with warm water (Hot pot).

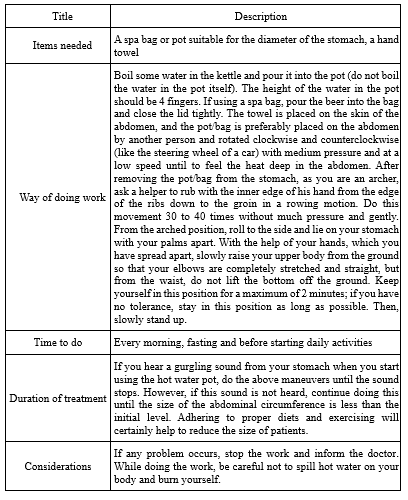

Guidelines were provided for creating a warm compress to be applied in the morning while fasting (Table 2 and Figure 1).

The patient was recommended to apply chamomile oil to the abdominal region twice daily (Table 1). Additionally, the patient was deemed eligible for visceral manipulation within the next 2 weeks. The second visit occurred on March 7, 2022. Over the course of these 2 weeks, the patient diligently followed the given instructions and prepared for the treatment of umbilical displacement. There was a noticeable reduction in symptoms such as flatulence, abdominal noise (gurgling), and excessive saliva (Ehiraq Riq). Furthermore, bowel movements increased from occurring every 2 to 3 days to once daily. The patient reported no significant change in fatigue and bruising compared to before. As a result, the patient was considered suitable for visceral manipulation. Initially, the patient's abdomen was subjected to a 15-minute application of 5-cm diameter glass cups to generate warmth. Inflatable cups were then strategically positioned around the umbilical region and on the stomach. Prior to manipulating the navel, the patient experienced pain in the left upper quadrant (LUQ) of the abdomen. However, following the abdominal visceral manipulation (performed in two rounds), the patient reported a 50% decrease in pain during the LUQ examination.

Discussion

Abdominal pain is a common issue that presents various causes, often posing challenges for health care providers in terms of diagnosis and treatment. In emergency departments, it is one of the most frequently reported concerns by patients, accounting for approximately 5%-10% of referrals. To establish an accurate diagnosis, a comprehensive history is crucial, including a detailed description of the patient's pain and associated symptoms. Additionally, a thorough assessment of the patient's medical, surgical, and social background can provide valuable insights for the evaluation process. The "PRASED" method, which stands for the patient's problem, history of the presenting problem, relevant medical history, allergies, systems review, essential family and social history, and drug use, can be employed by health care providers to effectively gather information regarding the patient's chief complaint, history of the presenting problem, relevant medical background, allergies, review of systems, important familial and social history, as well as medication usage (4).

Comprehensive patient evaluation involves addressing the patient's concerns, providing background information on the presenting issue, providing relevant medical history and allergies, reviewing systems, assessing important family and social backgrounds, and utilizing pharmaceutical substances. The primary objective of conducting an abdominal examination is to evaluate the patient's overall condition, which includes the initial assessment, identifying the location of intra-abdominal pain, and determining the etiology of extra-abdominal pain (4).

The general appearance and vital signs of the patient play a crucial role in differentiating diagnoses. Individuals with peritonitis typically exhibit immobility, while those with renal colic often display an inability to stay still. Certain maneuvers, although often overlooked, are valuable in assessing symptoms related to the underlying causes of abdominal pain. For example, Carnet's sign involves increased pain when the patient assumes a supine position, raises their head and shoulders off a surface, and contracts the abdominal muscles. This sign indicates abdominal wall pain. Other notable maneuvers include Murphy's sign for cholecystitis and Pessoa's sign for appendicitis (4).

In the diagnosis of abdominal pain, it is essential to perform a rectal and pelvic examination. A rectal examination can reveal fecal impaction, a palpable mass, or occult blood in the stool. Tenderness and fullness on the right side of the rectum may suggest appendicitis. The presence of cervical motion tenderness and peritoneal symptoms increases the likelihood of ectopic pregnancy or other gynecological complications such as salpingitis or a fallopian tube abscess (4).

The abdominal wall is composed of layers, including the skin, superficial fascia and fat, superficial sheath of the abdominal muscle, rectus abdominis, deep layer of the sheath, subperitoneal graft tissue, and peritoneum (2). Due to its unique position, the navel is connected to the muscles of the abdominal wall, diaphragm, and pelvis through the linea alba. It is directly connected to the bladder through the medial and lateral ligaments of the umbilicus, and it is connected to the liver through the round ligament of the liver (ligamentum teres hepatis). The peritoneum is located behind the navel and connects it to the digestive system, reproductive system, and urinary system. This structural integrity is crucial in Persian medicine, and any displacement of the umbilicus can result in various signs and symptoms, particularly in the abdominal region (2).

According to Iranian medicine sources, the navel is considered a significant point in the human body. Therefore, along with physical examination, the examination of the navel is also taken into account. The navel is connected to vital organs such as the digestive system and urogenital system through a rich neurovascular network and surrounding connective tissue (5-7).

In cases where there is unilateral or non-relative spasm of the abdominal muscles, the umbilical cord is pulled to one side, causing pressure on the blood vessels on that side. This leads to impaired blood supply on one side and hyperemia on the other side. During examination, the pulse below the navel is shifted to one side and becomes tender upon deep palpation (1,8,9).

It is crucial to determine the direction in which the navel has moved. If the navel moves downward, it can cause diarrhea. If it moves upward, it may result in symptoms such as nausea, loss of appetite, back pain, constant thirst, and abdominal pain (2).

The treatment of umbilical displacement in Persian medicine involves dietary measures, drug treatment, and medicinal practices.

One major limitation of this study is the absence of ultrasound examination prior to visceral manipulation. However, a notable strength of this article is the use of visceral manipulation in treatment, combined with herbal medicine, based on Persian medicine theory.

Conclusion

From the perspective of TPM, umbilical displacement (dislocation) is considered a pathological condition that is identified through historical analysis and physical assessment. It can be prevented through fundamental measures that promote well-being, and in cases of infection, remedial interventions can be pursued to alleviate it. Therefore, it is crucial to conduct further investigations in the field of manipulation within TPM to expand therapeutic approaches based on scientific evidence.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank the patient who gave permission to publish this case report in full and Dr Maryam Kavosi for editing the manuscript.

Funding sources

Not applicable.

Ethical statement

This article was approved by the Ethics Committee of Golestan University of Medical Sciences (Code: IR.GOUMS.REC.1402.414). Oral consent was obtained from the subject, and she was assured that his personal data would remain confidential.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author contributions

Masoumeh Norouzi Allahleh Korabi contributed to the preparation of the manuscript. Assie Jokar contributed to the design and editing of the manuscript and the study. Marzieh Qaraaty visited and managed the patient and contributed to the design of the study and preparation of the manuscript.

Treatment in traditional Persian medicine (TPM) is based on 3 principles: preserving health, nutrition, and medication and therapeutic measures. Among these therapeutic measures, visceral manipulation is a significant approach.

Umbilical displacement, referred to as "Taharok-e Sorre" or "Soghoot-e Sorre" in TPM texts (1), signifies the incorrect positioning of the umbilicus, characterized by its slipperiness, fallen state, or knotting (2). TPM scholars have expressed various opinions regarding umbilical displacement (Taharok-e Sorre). One of them suggests that it is caused by the movement of the abdominal muscles near the umbilicus, resulting from intense and sudden movements (1).

The factors causing umbilical displacement include impacts, slipping of the feet, and lifting heavy loads (3). Symptoms of umbilical displacement include intestinal pain, twisting of the umbilical cord in the abdomen, constipation, changes in bowel movements, loss of appetite, excessive unquenchable thirst, and the inability to palpate the artery below the displaced umbilicus (1).

Umbilical dislocation or displacement is linked to various symptoms, including diarrhea, constipation, abdominal pain, anorexia, anxiety, and depression (2). According to TPM, these symptoms arise from structural changes, such as physiological and anatomical alterations, as well as the accumulation of gases and fluids in the umbilical and tail region, whether momentary or permanent. Consequently, the foundation of treatment is based on reducing gas production and enhancing fluid analysis (1).

Methods

History and clinical examination based on conventional medicine

The patient is a 35-year-old married woman (G2P2Ab0L2NVD2) with a height of 164 cm, a weight of 78 kg, and a body mass index of 29.10 (indicating that she is overweight). She resides in Gorgan, Iran. The patient presented with complaints of pain in the upper and lower left side of the abdomen, constant and non-radiating, accompanied by a high appetite and abdominal fat. She sought treatment at the TPM health care center affiliated with Golestan University of Medical Sciences on 21 February 2022.

Gastrointestinal history:

The patient did not report any postural pain or its association with eating. She had been experiencing fatigue, bruising, and somnolence for approximately 1 year. The patient mentioned that around 5 years ago, after her second childbirth, she started experiencing an increased desire for food and accumulation of abdominal fat, along with symptoms of depression. She had been receiving treatment with sertraline until the time of referral. Additionally, for the past year, she had been experiencing soft bowel movements occurring once every 2 or 3 days without complete excretion.

The patient did not exhibit symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, anorexia, or urinary complaints. However, she expressed dissatisfaction with the quality and uninterruptedness of her sleep. Her typical sleep period is from 11 PM to 6 AM.

In terms of menstrual history, the patient reported irregular and fluctuating monthly cycles. The bleeding experienced was of moderate intensity, and the presence of clots and dark blood was noted.

Past medical history:

The patient mentioned a previous diagnosis of hyperlipidemia.

Drug history:

The patient had been regularly taking 75 mg of sertraline (brand name: Acentra) daily for 1 year to manage her depression. No information was provided regarding the use of tobacco, alcohol, or smoking.

Family history:

The patient reported a family history of high blood pressure in her mother.

Allergy history:

The patient has no known history of allergic reactions to medications, seasonal allergies, or food allergies.

Surgery history:

The patient underwent gallbladder removal and curettage procedures in the past.

History and clinical examination based on TPM

According to Salmannejad's temperament questionnaire, the patient's primary temperament (Mezaj) was determined to be hot and wet (Garm-o-Tar), with a score of 56 for warmth and 11 for wetness (4). The patient had a fat body, white facial skin, and dark brown eyes and hair. Additionally, for approximately 1 year, the patient experienced soft bowel movements occurring every 2 to 3 days without complete evacuation.

During the clinical examination, the patient exhibited abdominal pain and a palpable pulse around the navel.

Healthy lifestyle measures

The initial therapy session took place on February 21, 2022.

During the session, the patient was provided with health-conscious recommendations based on TPM practices. Due to the patient's inadequate and irregular sleep patterns, it was suggested that she establish a consistent sleep schedule, specifically from 10 PM to 6 AM, and avoid excessive daytime sleep. Furthermore, the patient was advised to engage in regular physical activity, avoid prolonged periods of inactivity, and limit the consumption of yogurt, buttermilk, pickles, cucumber, and tomato salad. It was recommended that the patient consume meals at a leisurely pace, thoroughly chewing her food. To reduce water intake, the patient was advised to follow a diet consisting of olives, steamed vegetables, grilled meat, and fresh produce. Additionally, the patient received guidance on managing anxiety through deep breathing techniques.

During the initial session, in addition to lifestyle recommendations, the patient was prescribed the following treatments:

After each meal, the patient was advised to take 2 tablets of Qors-e-Balgham, followed by 1 Iaraj Fighra capsule in the morning while fasting (Table 1). These should be consumed with warm water (Hot pot).

|

Table 1. Components of products prescribed for the patient

|

|

Table 2. How to use a hot water compress (Hot pot)

|

The patient was recommended to apply chamomile oil to the abdominal region twice daily (Table 1). Additionally, the patient was deemed eligible for visceral manipulation within the next 2 weeks. The second visit occurred on March 7, 2022. Over the course of these 2 weeks, the patient diligently followed the given instructions and prepared for the treatment of umbilical displacement. There was a noticeable reduction in symptoms such as flatulence, abdominal noise (gurgling), and excessive saliva (Ehiraq Riq). Furthermore, bowel movements increased from occurring every 2 to 3 days to once daily. The patient reported no significant change in fatigue and bruising compared to before. As a result, the patient was considered suitable for visceral manipulation. Initially, the patient's abdomen was subjected to a 15-minute application of 5-cm diameter glass cups to generate warmth. Inflatable cups were then strategically positioned around the umbilical region and on the stomach. Prior to manipulating the navel, the patient experienced pain in the left upper quadrant (LUQ) of the abdomen. However, following the abdominal visceral manipulation (performed in two rounds), the patient reported a 50% decrease in pain during the LUQ examination.

Discussion

Abdominal pain is a common issue that presents various causes, often posing challenges for health care providers in terms of diagnosis and treatment. In emergency departments, it is one of the most frequently reported concerns by patients, accounting for approximately 5%-10% of referrals. To establish an accurate diagnosis, a comprehensive history is crucial, including a detailed description of the patient's pain and associated symptoms. Additionally, a thorough assessment of the patient's medical, surgical, and social background can provide valuable insights for the evaluation process. The "PRASED" method, which stands for the patient's problem, history of the presenting problem, relevant medical history, allergies, systems review, essential family and social history, and drug use, can be employed by health care providers to effectively gather information regarding the patient's chief complaint, history of the presenting problem, relevant medical background, allergies, review of systems, important familial and social history, as well as medication usage (4).

Comprehensive patient evaluation involves addressing the patient's concerns, providing background information on the presenting issue, providing relevant medical history and allergies, reviewing systems, assessing important family and social backgrounds, and utilizing pharmaceutical substances. The primary objective of conducting an abdominal examination is to evaluate the patient's overall condition, which includes the initial assessment, identifying the location of intra-abdominal pain, and determining the etiology of extra-abdominal pain (4).

The general appearance and vital signs of the patient play a crucial role in differentiating diagnoses. Individuals with peritonitis typically exhibit immobility, while those with renal colic often display an inability to stay still. Certain maneuvers, although often overlooked, are valuable in assessing symptoms related to the underlying causes of abdominal pain. For example, Carnet's sign involves increased pain when the patient assumes a supine position, raises their head and shoulders off a surface, and contracts the abdominal muscles. This sign indicates abdominal wall pain. Other notable maneuvers include Murphy's sign for cholecystitis and Pessoa's sign for appendicitis (4).

In the diagnosis of abdominal pain, it is essential to perform a rectal and pelvic examination. A rectal examination can reveal fecal impaction, a palpable mass, or occult blood in the stool. Tenderness and fullness on the right side of the rectum may suggest appendicitis. The presence of cervical motion tenderness and peritoneal symptoms increases the likelihood of ectopic pregnancy or other gynecological complications such as salpingitis or a fallopian tube abscess (4).

The abdominal wall is composed of layers, including the skin, superficial fascia and fat, superficial sheath of the abdominal muscle, rectus abdominis, deep layer of the sheath, subperitoneal graft tissue, and peritoneum (2). Due to its unique position, the navel is connected to the muscles of the abdominal wall, diaphragm, and pelvis through the linea alba. It is directly connected to the bladder through the medial and lateral ligaments of the umbilicus, and it is connected to the liver through the round ligament of the liver (ligamentum teres hepatis). The peritoneum is located behind the navel and connects it to the digestive system, reproductive system, and urinary system. This structural integrity is crucial in Persian medicine, and any displacement of the umbilicus can result in various signs and symptoms, particularly in the abdominal region (2).

According to Iranian medicine sources, the navel is considered a significant point in the human body. Therefore, along with physical examination, the examination of the navel is also taken into account. The navel is connected to vital organs such as the digestive system and urogenital system through a rich neurovascular network and surrounding connective tissue (5-7).

In cases where there is unilateral or non-relative spasm of the abdominal muscles, the umbilical cord is pulled to one side, causing pressure on the blood vessels on that side. This leads to impaired blood supply on one side and hyperemia on the other side. During examination, the pulse below the navel is shifted to one side and becomes tender upon deep palpation (1,8,9).

It is crucial to determine the direction in which the navel has moved. If the navel moves downward, it can cause diarrhea. If it moves upward, it may result in symptoms such as nausea, loss of appetite, back pain, constant thirst, and abdominal pain (2).

The treatment of umbilical displacement in Persian medicine involves dietary measures, drug treatment, and medicinal practices.

One major limitation of this study is the absence of ultrasound examination prior to visceral manipulation. However, a notable strength of this article is the use of visceral manipulation in treatment, combined with herbal medicine, based on Persian medicine theory.

Conclusion

From the perspective of TPM, umbilical displacement (dislocation) is considered a pathological condition that is identified through historical analysis and physical assessment. It can be prevented through fundamental measures that promote well-being, and in cases of infection, remedial interventions can be pursued to alleviate it. Therefore, it is crucial to conduct further investigations in the field of manipulation within TPM to expand therapeutic approaches based on scientific evidence.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank the patient who gave permission to publish this case report in full and Dr Maryam Kavosi for editing the manuscript.

Funding sources

Not applicable.

Ethical statement

This article was approved by the Ethics Committee of Golestan University of Medical Sciences (Code: IR.GOUMS.REC.1402.414). Oral consent was obtained from the subject, and she was assured that his personal data would remain confidential.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author contributions

Masoumeh Norouzi Allahleh Korabi contributed to the preparation of the manuscript. Assie Jokar contributed to the design and editing of the manuscript and the study. Marzieh Qaraaty visited and managed the patient and contributed to the design of the study and preparation of the manuscript.

Article Type: Case report |

Subject:

Medicine

References

1. Shirooye P, Nabimeybodi R, Bahman M. Umbilicus dislocation in the view of Iranian Traditional Medicine. Journal of Islamic and Iranian Traditional Medicine. 2016;7(1):67-72. [View at Publisher] [Google Scholar]

2. Salmanian M, Hashem-Dabaghian F. Umbilical displacement: a mini review. Tradit Med Res. 2023;8(2):12. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

3. S-a-D A. Khazaen-al-Molook. Tehran: Iran university of Medical Science; Research Institute for Islamic and Complementary Medicine; 2005. p.120. [View at Publisher] [Google Scholar]

4. Govender I, Rangiah S, Bongongo T, Mahuma P. A primary care approach to abdominal pain in adults. S Afr Fam Pract. 2021;63(1):e1-5. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

5. Drake R, Vogl AW, Mitchell AW. Gray's anatomy for students E-book. Philadelphia: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2009. [View at Publisher] [Google Scholar]

6. Myers TW. Anatomy trains e-book: Myofascial meridians for manual therapists and movement professionals. China: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2020. [View at Publisher] [Google Scholar]

7. Fahmy M. Umbilicus and umbilical cord. Switzerland: Springer; 2018. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

8. Yosri MM, Hamada HA, Yousef AM. Effect of visceral manipulation on menstrual complaints in women with polycystic ovarian syndrome. J Osteopath Med. 2022;122(8):411-22. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

9. MA C. Exir- e Azam. Tehran: Traditional and Islamic medicine Institue; 1999. [View at Publisher]

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0).